Quadrilateral Cowboy belongs to the lately-minted genre of games where you code or script from within the game—though it’s a bit less breakable than Hack ‘n’ Slash, a bit less tactile and open-ended than SpaceChem or Infinifactory or The Magic Circle, and infinitely less obtuse than TIS-100.

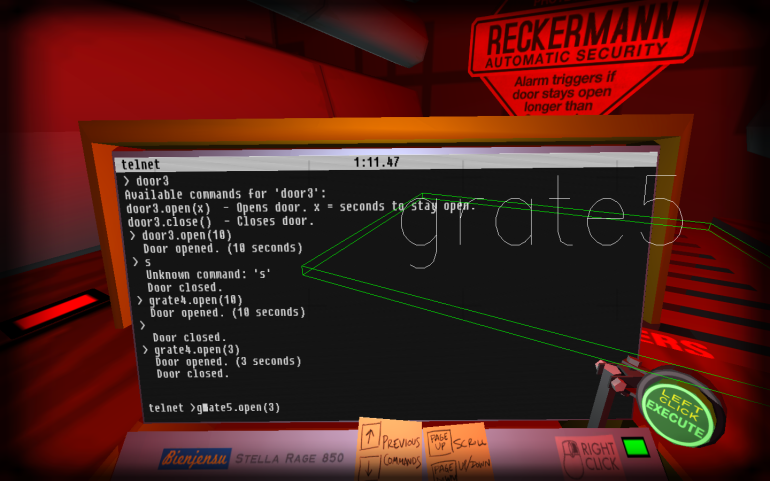

This game’s hacking distinguishes itself by being fluid, almost balletic. Sure, you’re typing legit text commands into a believably antique monochrome terminal. But that’s the choreography. Next comes the dance itself, spring-loaded commands fanning out like Esther Williams’ diving chorines, security systems disabling themselves for you like clockwork. You consider. You tinker. But then you perform.

Early in the game, you’re tasked with stealing a briefcase and smuggling it out of an office building. You enter from the roof, you work your way down, and once you grab the goods you’ve got ten seconds to reach the extraction point before the alarm sounds. This means writing out your commands in a string, so that the door to the vault and the skylight that leads to the roof will open and close at the proper moments—leave them open too long, and yep, the alarm will sound—with the right amount of waiting in between. Get this right, and you’re rewarded with the pleasure of juggling powers in Dishonered, crossed with the satisfaction of producing a valid loop in Infinifactory. It takes a certain easy grace to finagle all those doors and skylights, and soon enough all those cameras and laser grids (and especially those periods of waiting; those are what’ll get you).

As your toolset expands, so too do the opportunities for you to feel like a superspy (and then to fail miserably and feel like some schmuck in an unconvincing Catwoman costume, and then to regroup, reconsider, and perfect your superspy shtick). It’s definitely a game about aiming at flawless execution, as opposed to improvising in the face of chaos, but nonetheless you’re expected to learn through experimentation, and you’re welcome to be as reckless as you’d like, initially.

Occasionally, Quadrilateral Cowboy can be obtuse in ways it doesn’t quite intend. In the example above with the briefcase, I planned my escape at length, and pulled it off by the skin of my teeth, the skylight already starting to slide shut as I climbed through it to safety… only to find that I couldn’t complete the mission, because I was supposed to be going after another, much less heavily-guarded briefcase. And there was no going back for it with all manner of security hell breaking loose below.

Yeah, that felt bad.

But then I reloaded and breezed through the easier objective. And sure enough, my next task was to get that tricker suitcase way down on the ground floor, and this time I breezed through that, too. That felt good. I’ll take confusion over too-safe hand-holding any day—it’s just that since Quadrilateral Cowboy generally challenges and teaches you at every turn, following something like the playful extended tutorial structure of Portal, those scattered moments of bad conveyance do land with a distracting thud.

But when the game sings, it nails the cyberpunk ethos, insofar as it makes typing bits of code feel both puissant and cool.

I think this is probably the feeling that Watch_Dogs was going for, though there it got lost in pedantic sidequest signposting and plotty Potemkin cinema. (In big splashy tentpole videogames, cinematic is frequently a synonym for non-interactive and/or expensive). Quadrilateral Cowboy, by contrast, is rugged and abstract, its narrative flair not just superficially cinemaesque but genuinely cinematic, with careful framing, economical world-building, and bold jump cuts.

Tonally and aesthetically, this isn’t rote cyberpunk, but a heady blend of lead developer Brendan Cheung’s many longstanding preoccupations. The game takes place in the same spy-strewn retro-future dystopia as Thirty Flights of Loving and Gravity Bone (not to mention Cheung’s earlier Barista and Citizen Abel games) and it employs the same squared-off minimalism, the same richly lived-in spaces, and the same pithily-drawn intimacy between its characters. Like those previous efforts, Quadrilateral Cowboy venerates heists and the clever subversives who pull them off—tight-knit weirdos smart enough to think and plan their way through just about any situation, but cocky and adventuresome enough to end up overwhelmed anyway.

It’s the meatiest game that’s ever taken place in this world of Cheung’s, not to mention the one with the most gameplay, in the strict Richard Terrell sense. Quadrilateral Cowboy absorbs you in the way the best coding-within-the-game games do, and lingers in your mind the way that Thirty Flights of Loving does.

It’s a game that delights in doing a lot with a little, and in giving you back more than what you put in, both mechanically and emotionally.